I’m late to the slam movement, but I am fast falling in love. I introduced two of my classes to it this semester, and several students and I now share new poems that we find with each other. I’ll be honest though, slam poetry is risky.

Part of what defines it is the fact that it is raw emotion about painful events–and such raw emotion is rarely pretty or grammatically correct or edited for polite society. Slam poetry is equal parts performance, metaphor, pacing, story-telling, and advocacy. It will sucker punch you when you least expect it, either with its painful honesty or its biting ironic wit.

Part of what defines it is the fact that it is raw emotion about painful events–and such raw emotion is rarely pretty or grammatically correct or edited for polite society. Slam poetry is equal parts performance, metaphor, pacing, story-telling, and advocacy. It will sucker punch you when you least expect it, either with its painful honesty or its biting ironic wit.

Below are five of my favorite slam poems, all of which I have played in my classroom. Yes, the language is often sailor-like and salty, but that’s part of their power. Slam poetry is about letting go, and letting people who don’t know your pain or frustration share it.

(1) Taylor Mail: If you’re a teacher, and you haven’t been privvy to Taylor Mali’s  “What Teacher’s Make,” you’ll want to bookmark this and watch it about halfway through test season (what we used to call ‘spring.’) It’s statement of what teachers really do, and what we really make. Mali’s other work is great, but as a middle school teacher, he sums up why we do what we do, and does it with power and pizazz. Here’s the text of it, but you MUST watch him perform it. Goosebumps. I promise. (You can find Mali on Twitter at @

“What Teacher’s Make,” you’ll want to bookmark this and watch it about halfway through test season (what we used to call ‘spring.’) It’s statement of what teachers really do, and what we really make. Mali’s other work is great, but as a middle school teacher, he sums up why we do what we do, and does it with power and pizazz. Here’s the text of it, but you MUST watch him perform it. Goosebumps. I promise. (You can find Mali on Twitter at @

(2) Janette McGhee Watson: If you’ve ever wanted to wander through a woman’s head  and find out what heartbreak and weak and absent fathers do to our psyches, “I Waited for You” by Janette McGhee Watson will take you there. Unapologetically and artistically, her poem is her wedding vows, and they are forceful and brutally honest. I have so much respect for her; it’s a ten minute treatise on why she is who she is, and why she is marrying the man in front of her, and it is as beautifully painful as anything you’ll see in a long time. You’ll need to watch this a few times to get all of it, as her rapidfire word play is sometimes difficult to catch, but oh, is it ever worth it! You can find her and more of her work here.

and find out what heartbreak and weak and absent fathers do to our psyches, “I Waited for You” by Janette McGhee Watson will take you there. Unapologetically and artistically, her poem is her wedding vows, and they are forceful and brutally honest. I have so much respect for her; it’s a ten minute treatise on why she is who she is, and why she is marrying the man in front of her, and it is as beautifully painful as anything you’ll see in a long time. You’ll need to watch this a few times to get all of it, as her rapidfire word play is sometimes difficult to catch, but oh, is it ever worth it! You can find her and more of her work here.

(3) Jesse Parent – “To the Boys Who May One Day Date My Daughter”  is just flat funny. Teenagers will love it because it’s a dad’s message to boys who, as the title says, may want to date his daughter. It’s a message every parent has thought at some point, and as a teacher, I think it’s a very cool thing for our kids to know that this is how we feel about them. Funny, threatening, loving, and hopeful, it’s great fun, with only a little bit of controversial content. (Jesse tweets @jesseparent.)

is just flat funny. Teenagers will love it because it’s a dad’s message to boys who, as the title says, may want to date his daughter. It’s a message every parent has thought at some point, and as a teacher, I think it’s a very cool thing for our kids to know that this is how we feel about them. Funny, threatening, loving, and hopeful, it’s great fun, with only a little bit of controversial content. (Jesse tweets @jesseparent.)

(4) Amina Iro and Hannah Halpern (@hanhalp), the two girls who perform this poem, have taken their personal experiences and differences and made the point that those things aren’t all that important in the grand scheme of things. With the Middle East still (always?) in the forefront of the news, their poem is and likely will be, timely for a long time. Check out their take on the Arab-Israeli conflict here.

(5) As a trans-racial adoptive mom, Javon Johnson’s “cuz he’s black” broke my  heart, and forced me to look at my son differently. Every person of color in the room will nod and agree, even if their white peers don’t. With so much talk about racism in the media today, it’s important to remember that you cannot dictate to another person what their own experience is. This poem helps teach that lesson. You can connect with Johnson on Twitterat @javonism.

heart, and forced me to look at my son differently. Every person of color in the room will nod and agree, even if their white peers don’t. With so much talk about racism in the media today, it’s important to remember that you cannot dictate to another person what their own experience is. This poem helps teach that lesson. You can connect with Johnson on Twitterat @javonism.

6. Kai Davis: This last one might require special permission to use in the classroom depending on where you are because of the ferocity of the language, but it is so worth it. Kai Davis’s “I Look Like” has a lot of f-bombs and n-words, but the message and the performance and the wordplay are near perfection. It’s about the judgement faced by smart kids of color by both their white and black peers, and how this one spunky young woman refuses to sell out to anyone. Kai tweets at @KaiDavisPoetry.

depending on where you are because of the ferocity of the language, but it is so worth it. Kai Davis’s “I Look Like” has a lot of f-bombs and n-words, but the message and the performance and the wordplay are near perfection. It’s about the judgement faced by smart kids of color by both their white and black peers, and how this one spunky young woman refuses to sell out to anyone. Kai tweets at @KaiDavisPoetry.

Slam poetry’s increasing popularity makes it an amazing classroom tool, and because of its tendency toward performance, self-evaluation and clever phrase turning, can appeal to a wide range of people. However: as a teacher, be cautious. These poems and their honesty and salty language are not for every classroom.

If I’ve missed a good one, let me know in the comments!

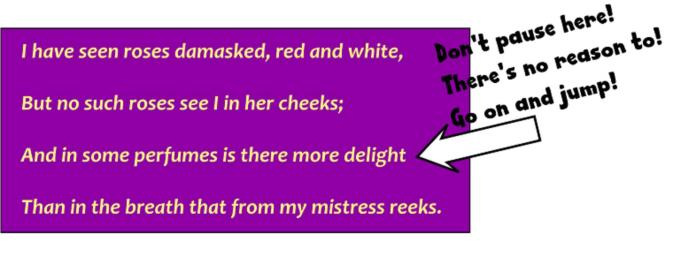

Today’s lesson on writing in 10th grade ELA was on eliminating unnecessary words and phrases. My favorite high school teacher called it “eliminating the deadwood,” and in today’s class, my standard, “Don’t waste your reader’s attention span on words they don’t need to read” was not explanation enough for one of my students.

Today’s lesson on writing in 10th grade ELA was on eliminating unnecessary words and phrases. My favorite high school teacher called it “eliminating the deadwood,” and in today’s class, my standard, “Don’t waste your reader’s attention span on words they don’t need to read” was not explanation enough for one of my students.